IRS Issues Final Regulations on Portability

The IRS recently issued final regulations (effective June 12, 2015),[1] clarifying the application of the “portability” rules – one of the relatively newer provisions relating to federal estate and gift tax (the “transfer tax”). The transfer tax applies with respect to certain gifts made by an individual during his/her lifetime and to assets included in an individual’s estate upon death. In 2012, Congress effectively changed the estate planning landscape by making certain taxpayer-friendly provisions a permanent fixture of the tax code. One such provision colloquially is referred to as “portability.”

In order to fully understand portability and its impact on estate planning, one must have a foundational understanding of transfer taxes generally.

The Basics of Transfer Taxes:

- Transfer taxes apply when one’s taxable estate (which includes lifetime gifts) exceeds the exemption amount. Currently, the exemption amount is $5.43 million. Therefore, a person can gift during his/her lifetime, or leave an estate with, assets valued at $5.43 million, without incurring any transfer tax liability. The $5.43 million exemption amount is the highest in the history of the estate tax and that amount is scheduled to increase annually based on inflation rates. As you may imagine, estate tax liability is applicable to only approximately .5% of all estates in the United States.

- Lifetime gifts and bequests upon death to a spouse and/or charity are wholly deductible for estate tax purposes and such transfers do not impact an individual’s exemption amount.

- Presently, an individual can make an unlimited number of completely tax-free gifts to anyone so long as the total gifts to any individual recipient does not exceed $14,000 during a calendar year.

The Basics of Portability:

Portability allows a surviving spouse to use his or her Deceased Spouse’s Unused Exemption Amount (“DSUEA”). Prior to portability, the estate and gift tax exemption was personal to an individual and could not be passed to that individual’s spouse. If the lifetime exemption was not used, it was lost. In other words, before the advent of portability, it was a “use it or lose it” proposition. Now, if portability is elected (discussed further below), a surviving spouse essentially can double his/her estate tax exemption amount from $5.43 million to $10.86 million (assuming no exemption was previously used by either spouse).

- Example: Irwin dies on June 15, 2015, leaving his wife, Debbie, an estate valued at $7.5 million. Debbie has her own assets, valued at $3 million. Portability allows Irwin’s fiduciary (executor or trustee) to preserve Irwin’s unused estate tax exemption by adding it to Debbie’s available exemption. Debbie would now have her own personal exemption of $5.43 million and Irwin’s unused exemption of $5.43 million for an aggregate exemption amount of $10.86 million. Debbie can apply the combined exemption amount to future gifts during her lifetime or allow this increased exemption amount to be used at the time of her death to reduce or eliminate her transfer tax liability. Prior to portability, however, under the same circumstances and without implementing additional lifetime planning, Debbie, would have an estate worth $10.5 million and an exemption amount of only $5.43 million resulting in an approximate $5 million taxable estate and the unpleasant reality of a nearly $2 million federal transfer tax liability.

Portability Clarified:

With its issuance of final regulations the IRS clarified the application of the portability rules thereby solidifying portability logistics and processes that previously were unsettled. As a result, administrators of many estates that prior to portability (and the clarification of the final regulations) would not otherwise have contemplated filing an estate tax return are now faced with an additional decision and task. The more relevant regulations include:

- Timely Election Required: Unused exemption is not automatically “inherited” by the surviving spouse. In order for a surviving spouse to take advantage of portability, an election must be made on a “complete, properly prepared and timely filed” estate tax return of the deceased spouse. This is true even if the decedent’s estate would not otherwise be required to file because it is within the $5.43 million exemption. In fact, irrespective of a deceased spouse’s or a couple’s net worth, it would seem that every fiduciary of a decedent who was survived by a spouse needs to seriously consider filing an estate tax return where the decedent’s exemption amount was underutilized, for the sole purpose of preserving the remaining exemption amount for the surviving spouse.

- No Short Form Tax Return: The IRS’s final regulations provide that an election for portability is only valid if elected on an otherwise timely and properly filed return. Thus, the final regulations rejected a suggestion that the service provide a “short form” estate tax return for taxpayers who are filing solely to elect portability, although filing an estate tax return solely for the purpose of preserving the DSUEA might prove to be time consuming and costly.

- Effect of Re-marriage: A surviving spouse can only use the DSUEA of his or her last spouse to die. For example, let us suppose that Irwin’s fiduciary makes a valid portability election. Debbie then remarries Sam who has an estate of $5.43 million. Sam predeceases Debbie and leaves his entire estate to his children. Sam’s estate tax exemption is sufficient to allow these assets to be distributed tax-free. However, since Sam is now Debbie’s last deceased spouse, Irwin’s exemption is lost. And, since Sam, who was Debbie’s last deceased spouse, used his entire exemption amount, Debbie (unless she marries for a third time) would be left with no DSUEA to use during her life or at her subsequent death and would only have her personal exemption amount.

Prior to portability, the only way to fully utilize a married couple’s combined exemption amount was to make sure that (i) each spouse had sufficient assets titled in his or her name and (ii) that these assets did not pass to the surviving spouse in a manner in which they would be includible in the surviving spouse’s estate at his or her later death. Typically, the planning would include the creation of a “shelter” or “bypass” trust under the will of the first spouse to die, for the benefit of the couple’s children and surviving spouse (but not qualifying for the marital deduction from estate tax). If this was not done, part or all of the exemption of the first spouse to die would be wasted.

Portability and the States:

All of you who stopped reading this article upon hearing mega-wealthy astronomical figures of $5 million and $10 million – now you can tune back in.

While portability offers a taxpayer-friendly solution in the context of federal transfer taxes, so far, for the most part, states (that have transfer taxes) have not adopted the portability concept (with the exception of Delaware and Hawaii). Accordingly, the state estate tax exemption amount (which in New York is currently $3.125 million and in New Jersey is only $675,000) cannot be inherited by an individual’s spouse and will be “lost” if not used. Therefore, it may be advisable to continue to use the “credit shelter” trust or similar strategies in order to take advantage of the state tax exemption of the first spouse to die. Irrespective of sheltering unused exemption, a trust remains advantageous for the traditional benefits that a trust offers, including asset protection for the surviving spouse, restricting transfers by the surviving spouse and general oversight of assets even after death. A trust also provides additional tax benefits, such as allowing assets transferred to the trust to appreciate “outside” the estate of the surviving spouse and giving the taxpayer the ability to “use” another exemption which would otherwise be unpreserved by the portability election and wasted upon the first to die.[2]

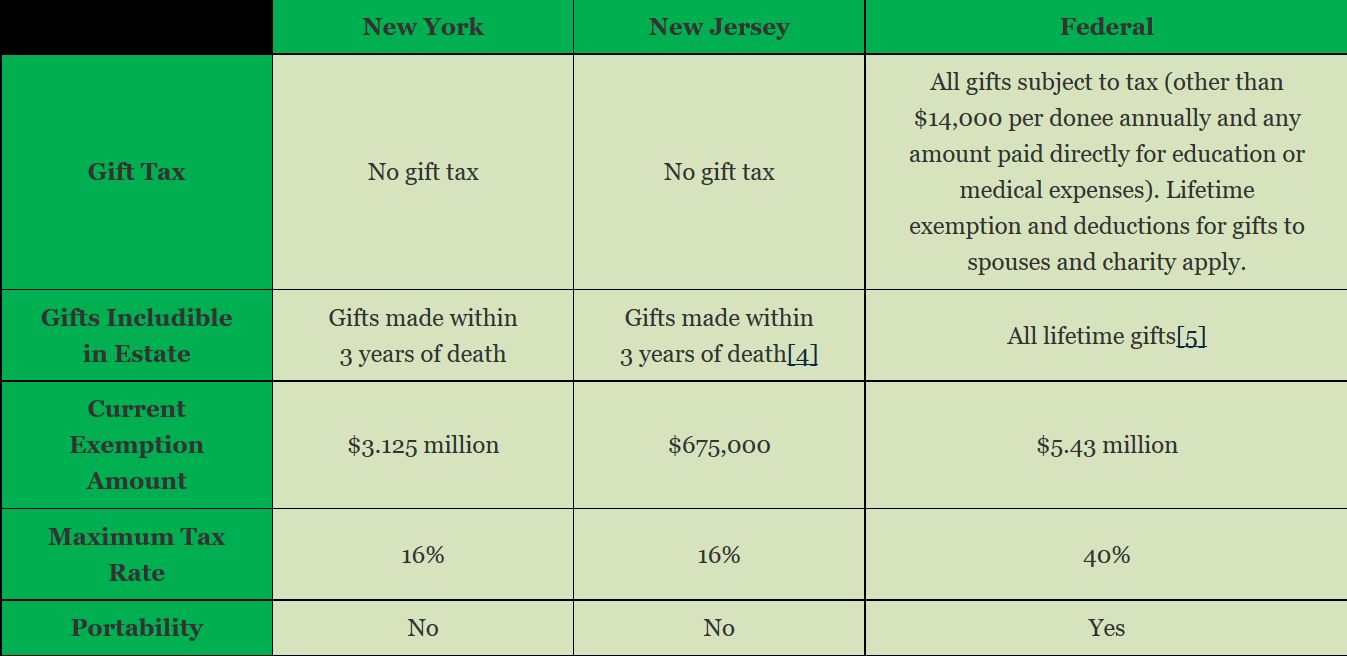

Although, New York and New Jersey disadvantage taxpayers with lower estate tax exemption amounts and no portability provision, their respective transfer tax system is less burdensome than their federal counterpart in other areas.

- Lifetime Gifting: Neither New York or New Jersey tax gifts made during one’s lifetime. In both states, only the value of lifetime gifts made within three years of death will be included in the decedent’s estate for purposes of determining state estate tax liability.[3] All prior gifts made during a person’s lifetime will be tax free.

- Estate Tax Rates: For federal estate taxes, every dollar of an estate in excess of the exemption amount is taxed at a maximum tax rate of 40%. On the other hand, New York and New Jersey estate taxes have a maximum tax rate of 16%. The effective tax rates for these states are typically much lower, depending on the amount of assets exceeding the exemption amount.

* * * * *

Conclusion:

Portability can be a very effective and efficient tool for estate tax savings. Determining whether reliance on a portability election is appropriate for a particular situation is a relevant consideration while both spouses are living and/or following the death of the first spouse.

We are available to advise our clients with respect to portability or to discuss any other estate planning and estate administration matter.

The information contained in this article is for general information purposes only. It is not intended as professional counsel and should not be used as such.

Baruch (Brian) Y. Greenwald and Hillel D. Weiss are the founding members of Greenwald Weiss Attorneys At Law, LLC, a New York and New Jersey based law firm focused on estate planning and related matters. If you have any questions relating to this article or would like additional information regarding estate planning, please visit www.greenwaldweiss.com or contact Baruch (Brian) at (718) 564-6333 or bgreenwald@greenwaldweiss.com, or Hillel at (732) 526-6333 or hweiss@greenwaldweiss.com.

Yisroel Katz, a summer intern at Greenwald Weiss and 1L at Brooklyn Law School, assisted with the research for and writing of this article.

- [1] 80 F.R. 34279; available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/FR-2015-06-16/2015-14663

- [2] We are talking about the generation-skipping transfer (“GST”) tax exemption under Section 2631 of the Internal Revenue Code – a whole other topic.

- [3] But see note 4.

- [4] Even so, with respect to NJ estate tax, in many cases it is nonetheless advisable to engage in lifetime “deathbed” gifting, since such gifting will reduce the estate subject to state estate tax. The explanation for how this operates is complex and beyond the scope of this article.

- [5] Since 1976. The effect of this rule is to apply the current tax rate in effect at the decedent’s death to all gifts made during life.

Recent Comments